Poor House

For many people in nineteenth-century Halifax, life was exceptionally challenging. In many cases the indigent and mentally ill faced tremendous obstacles in securing food and lodging. Like other North American cities, alcohol was also a widespread societal problem. Many of the most vulnerable in Halifax were generally sent to the poor house, and usually died as "inmates". Although a visitor will find no markings, Holy Cross Cemetery is the final resting place for nearly twenty thousand of these individuals.

The poorhouse (or poors’ asylum) was, as historian Judith Fingard illustrates, “an alternative to the prison,” and a place of “final resort.” Its inhabitants represented the downtrodden of society. Some were insane, others were petty criminals, but most were elderly, physically handicapped, seasonally unemployed, or unwed mothers. Those inmates who were physically able were put to work in the kitchen, hospital, or “stoking the furnaces.” In fact, the poor house essentially functioned as a self-contained society. The inmates worked in the vegetable gardens, or tended to the livestock in the barns. The access meat and milk products were sold in Halifax. According to Cynthia Simpson, inmates were “fully expected to contribute to their subsistence through hard labor."

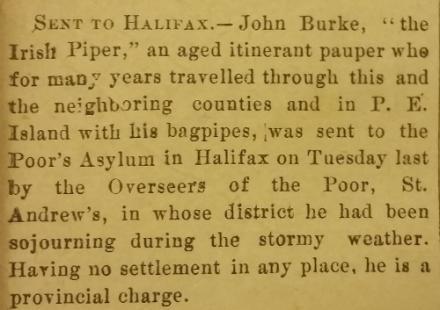

[The Casket (Antigonish), March 3 1892. Burke died on 21 January 1893]

In 1868, the firm Peters, Blaiklock & Peters, took the contract to construct a large poor house on the corner of Robie and South Streets. The first home in Halifax had been located on the spring garden road, but it soon proved inadequate and for many years, petitions were written proposing the construction of a new and more spacious building. The Acadian Recorder of 17 April, 1867 carried a notice of tender for “the erection of a brick building, on the south common.”

Henry Peters (buried in Holy Cross) employed the designs of David Sterling, whose plans called for a building in the form of a “latin cross, with four wings descending from a central building, which measured 180 feet long, 50 feet wide, and four stories high.” The construction was completed near Christmas 1869, and according to Halifax historian Peter McGuigan, the new poor house was “a noble monument to charity and benevolence... it was a combination of an old-age home, an asylum for poor families, a minor hospital, a refuge for the mentally and physically disabled, and a place for inebriates.”

On 6 November 1882 the poor house was the scene of a tragic and deadly fire. The inferno broke out in the kitchen area of the building (in the basement where twenty cord of wood was stored) around midnight. It quickly spread up the elevator shaft and into the dormitories, which caused “utmost terror among the four or five hundred inmates.” That evening the wind was from the north-west and the first witnesses to the scene saw smoke pouring out of the windows, but could not see flames.

In the west wing of the building women and children, both young and old, were breaking the windows in a desperate attempt to reach safety. Fearful that they would throw themselves out of the building, a man took an axe and knocked down the door. Within seconds, “out came a procession of women nursing little infants,” along with the elderly. There was panic, and many of those fleeing the west wing were in terror. When the west wing was cleared, it became obvious that the most helpless were all in the upper wards of the building. A number of brave bystanders rushed into the burning asylum to help evacuate those on the higher levels. By this time the fire had reached the hospital on the top floor and smoke poured out of the windows.

The city of Halifax was shocked by the horror of the fire. On 8 November, the Halifax Morning Chronicle declared the holocaust to be “the most distressing affair of the kind that ever occurred in Nova Scotia.” Thirty-one people lost their lives, thirty burned to death, while another man succumbed to his injuries in the barn.

Those from the Irish community that died were:

Thomas Murphy (aged 56 and native of Halifax)

William Brennan (aged 52 and native of St. Margaret’s Bay)

Anne Ahern (aged 50, Ireland)

Christina Kiely (aged 88, Ireland)

Mary Kavanagh (aged 75, Ireland)

Mary Leahy (aged 65, Ireland)

Anne Pritchard (aged 78, Ireland)

Ellen Ryan (aged 63, Ireland)

Mary O’Ronark (aged 20)

Catherine Meagher (aged 59, Halifax)

On 16 December 1884, the ruins of the poor house were “blown down” by the Royal Engineers, and a new building was constructed on the same spot.

Many of the inmates of the Halifax Poor House were of Irish descent. Judith Fingard demonstrates that in the 1830s, the Irish-born in the poorhouse were second in number only to the Halifax-born. In fact, in 1868, John Francis Maguire Irish M.P. wrote in his influential book, The Irish in America that “two-thirds” of the Halifax inmates were Irish, most of whom “owed their social ruin to the one fruitful cause of evil to the Irish race-that which tracks them across the ocean, and follows them in every circumstance and condition of life-that which mars their virtues and magnifies their failings-that which is in reality the only enemy they have occasion to dread, for it is the most insidious, the most seductive, and the most fatal of all-drink.”

The first poor house residents were buried in Holy Cross in December 1843. On the 17th, Patrick Walsh, a thirty-eight-year-old laborer from County Cork was interred. On the following morning, Anthony Carroll, aged fifty-six, and a native of County Kilkenny, followed. Over the next sixty years, thousands more would join them. While the majority of the poor house burials in Holy Cross came from the Irish community, there were four of African descent and six of Mi’Kmaq heritage, including the ninety-six-year-old Margaret Toney, who was buried on 22 January 1889.

Sadly many children spent much of their young lives in the poor house, and those that died at a young age knew no other abode. There are hundreds of unhappy cases in the burial records. The first child interred was Elizabeth Barron, who was buried on the second day of January 1844 at the age of three. The last child buried in Holy Cross during the nineteenth-century was Bernard Townsend. He died in 1895 of “convulsions” and was buried after only five days of life. Poignantly, the boy had not lived a single week and yet was labeled in the burial records as a “pauper.”

Further Reading:

Judith Fingard, The Dark Side of Life in Victorian Halifax (Halifax: Pottersfield Press, 1989).

Judith Fingard, “The Relief of the Unemployed Poor in Saint John, Halifax, and St. John’s, 1815-1860,” Acadiensis, V, 2 (Autumn 1975): 32-50. (View Fingard Article)

Judith Fingard, “Attitudes towards the Education of the Poor in Colonial Halifax,” Acadiensis, II, 2 (1973): 15-42. (View Fingard Paper)

John Francis Maguire, The Irish in America (New York, D & J Sadler, 1868).

Peter McGuigan, Historic South End Halifax (Halifax: Nimbus, 2007).

Cynthia Simpson, “The Treatment of Halifax’s poor house dead during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries,” (M.A. Thesis, Saint Mary’s University, 2011). (View Simpson Thesis)

The Professional papers of the Corps of royal engineers. Royal engineer institute occasional papers, Paper IV, Demolition of Ruins of Poor House, Halifax N.S., pp.75-80.