Irish Culture

Many of the Irish men and women buried in Holy Cross Cemetery made significant contributions to the culture of Halifax. Unquestionably Halifax had a Hibernian spirit that endorsed old Ireland, while remaining steadfast in its loyalty to the British Empire.

[Richard John Uniacke (1753-1830)]

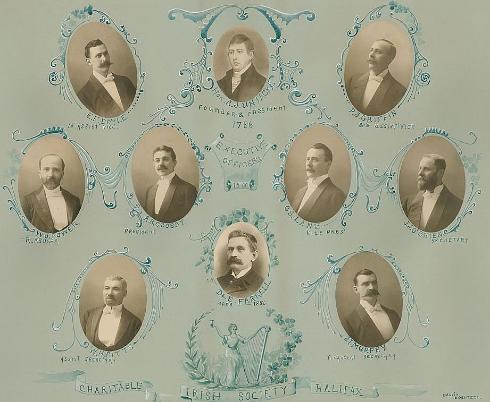

The most important purveyor of Irish culture in the city was the Charitable Irish Society of Halifax (CIS), which was founded on 17 January 1786. Like similar benevolent societies in Newfoundland and New Brunswick, the CIS was organized primarily by Protestants, and was tasked with funneling financial and material assistance to indigent Irish residents. The earliest membership of the society was closely affiliated with the colonial elite, as the solicitor-general (later attorney-general), Richard John Uniacke, served as the inaugural president. Important government officials were treated to extravagant dinners, and loyal toasts were made to their monarch.

"THURSDAY the sons of St. PATRICK did credit to their Saint, and if his spirit was hovering over them, it would have been gratifying to find his progeny possessing undiminished gifts of hospitality, liberality, and conviviality—we could not help making the contrast between them and their guests—with a few exceptions the songs from the Irish were all English—and their guests gave them Scotch and English airs in return! – the Dinner was excellent, the Wine good, the President unrivalled, the Toasts appropriate and inimitable; we hope to see them in print." [Acadian Recorder, March 1814]

Besides offering charity to the poverty-stricken, the CIS was also a important social organization. It offered Halifax’s Hibernian population a number of “happy occasions” in which to express a national feeling for Ireland. The CIS obtained various flags, banners and paintings, which they employed during public parades and celebrations. Such insignias became commonplace within the garrison city. In celebration of Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838, for instance, CIS members marched with a harp pinned to their breasts and a shamrock on their hats (they also hosted a “hospitality tent”). When Victoria was married to Prince Albert in 1840, the CIS held a dinner; while a High Mass was offered at St. Mary’s Cathedral.

By the 1840s, the Irish Catholic community was undergoing a process of maturation. In a protracted battle with their Scottish Bishop, William Fraser, a local Irish Catholic leadership emerged within the community, which succeeded in its aspiration to attain both an Irish diocese and an Irish prelate. In the following decades there was a great expansion in religious and lay voluntary associations, and an explosion of institutional growth. This maturation of the Irish middle classes was reflected in the CIS. By 1848, half of the membership still came from the professional ranks, but many new members were artisans and workers. Most importantly, by the end of the 1840s, the CIS was almost wholly Roman Catholic.

In his study of the immigrant generation of Irish Halifax, Terrence Punch suggests that in the mid-nineteenth century the CIS was a vehicle for immigrants to “help their careers and assist their search for general acceptance in Halifax.” In other words, membership in the CIS was a tool to assist upward mobility. As the society became more aggressively middle class, it began to take a more active political role within Halifax society (when Daniel O’Connell died the Society mourned for a month). This assertiveness occasionally created sectarian animosity within the city. During the Crimea War, for instance, CIS President, William Condon, entered into a protracted feud with the society’s former president, Joseph Howe, over the recruitment of Irish labourers in the United States for the British Army. The dispute cumulated in the Gourley Shanty Riot, the fall of the provincial government, and the creation of the ill-fated “Protestant Alliance”.

Yet, benevolence and companionship remained at the core of the CIS. St. Patrick’s Day celebrations were a major part of the Halifax social calendar. In 1856, at an early hour, the membership, preceded by the band of the 76th Regiment, paraded through the town to St. Patrick’s church, where the Panegyric of St. Patrick was delivered by Archbishop Walsh. A dinner took place in the evening, at Masonic Hall, “when a large number of the ‘Irish Society’s’ members, along with numerous guests, sat down to a table prepared and furnished in Nichols’ best style.” A person who was present described the festival as an affair at which “they had excellent wine and very bad speeches.”

The St. Patrick’s Day celebrations were usually followed by an Irish Society Ball. In 1856 the Ball was held “in great style” at Mason’s Hall. According to the Acadian Recorder, “upwards of six hundred persons were present on the occasion.” Again, the Band of the 76th Regiment was present and delighted the Company with its music. The supper was served “in the Eastern wing, below stairs, a little after 12 o’clock; but many of the gayer members of the Company continued to trip it ‘on the light fantastic toe’ until near broad daylight.”

Throughout the nineteenth-century the CIS remained the most important Irish organization in Halifax. It also remained a male organization. Women first attended St. Patrick’s Day banquets in 1938, while the society did not authorize its first female member until 1982. Under, the O’Connell banner (which currently hangs in the Patrick Power Library at Saint Mary’s University), the men and women of the Charitable Irish Society of Halifax continue their important work in the city, hold an annual St. Patrick's day parade, fund various scholarly enterprises, and labour to maintain the Hibernian culture of Halifax.

Further Reading:

Brian C. Cuthbertson, “Uniacke, Richard John,” DCB, Volume VI (1987).

Bonnie Huskins, “From Haute Cuisine to Ox Roasts: Public Feasting and the Negotiation of Class in Mid-19th-Century Saint John and Halifax.” Labour/Le Travail 37 (Spring 1996): 9-36. (View Huskins Article)

A. J. B. Johnston, “Nativism in Nova Scotia: Anti-Irish Ideology in a Mid-Nineteenth-Century British Colony.” In Thomas P. Power (ed.)The Irish in Atlantic Canada 1780-1900 (Fredericton, New Brunswick: 1991): 23-29.

Peter T. McGuigan, Irish: Peoples of the Maritimes (Tantallon: Four East, 1991).

Terrence Punch, Irish Halifax: The Immigrant Generation, 1815-1859 (Halifax: Ethnic Heritgae Series, 1981).

H.L. Stewart: The Irish in Nova Scotia: annals of the Charitable Irish Society of Halifax (1736-1836), (Kentville: Kentville Publishing Co, 1949).

David Sutherland, “Voluntary Societies and the Process of Middle-class Formation in Early-Victorian Halifax, Nova Scotia.” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association/ Revue de la Société historique du Canada Vol. 5 No. 1 (1994): 237-263.