Building a Cemetery

The 1840s were a transformational period for the Irish Catholics of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Although the early Catholic community struggled institutionally, by the middle decades of the nineteenth-century, there were improvements in ecclesiastical governance, Catholic institutions, an increase in the number and quality of clergy, the arrival of two orders of women religious, and a sudden flowering of Irish associational life. Moreover, the Irish Catholics of Halifax were locked in a protracted struggle with their bishop, William Fraser, and the Highland Catholics of eastern Nova Scotia, which would result in the division of Nova Scotia in 1844 into two dioceses; Arichat for the Scots and Halifax for the Irish.

[Lithograph of Holy Cross. J.S. Clow, 1849]

The construction of Holy Cross cemetery served two important purposes. Firstly, it met an obvious sanitation requirement. Until 1843, deceased Roman Catholics were buried in St. Peter’s graveyard next to St. Peter’s Church (replaced by St. Mary’s in 1829), but that site had proven inadequate to meet the needs of a growing population. In 1843, facing a health crisis, local authorities provided crown land to both Catholic and Protestant communities on which to build new cemeteries (Camp Hill cemetery was constructed in 1844). Secondly, Holy Cross cemetery rallied the Irish community around a collective construction effort that raised the profile of Roman Catholicism in the imperial port town. Intuitively, Bishop William Walsh (1804-1858), recognized that such a significant upgrade in Catholic infrastructure would not only signify the transformation of the Irish in Halifax, but it would also signal to his colleagues and superiors in Arichat and Rome that his community had major capabilities.

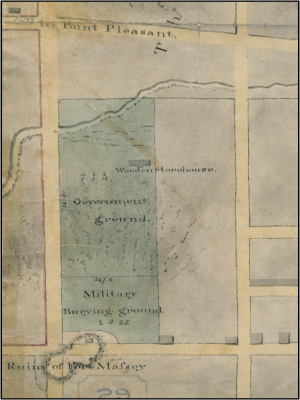

In the warm months of July, August, and September 1843, the Hibernian Catholics held three majestic and well attended processions. With colorful flags and banners, thousands of parishioners paraded from St. Mary’s Cathedral to the site of the new cemetery; the former government property adjacent to the Fort Massey burial ground. Each procession had a well-defined purpose. The first procession was to “enclose, drain, level and prepare the ground.” Bishop Walsh, with site plan in hand, directed the church wardens and led the work crews. In that single day, the multitude of workers constructed a bridge over a small brook at the entrance of the grounds which they named “St. Ann’s Bridge”. They also built a large gate called “St. Joseph’s Gate,” and a reservoir named in honor of St. Patrick. As the sun began its descent, Bishop Walsh stood at the center of the large crowd, and made an exuberant speech. According to the Irish nationalist paper, the Register, Walsh concluded his remarks “amid the most deafening and long continued cheers of applause."

In August a second procession was organized to construct a chapel, which was named “Our Lady of Sorrows Chapel” (also known as Our Lady of Dolours). Although some prefabrication work had been done in advance, the chapel was essentially constructed in a single day, which was the talk of Halifax at the time. On the 17th of September, 1843 (the Feast of the Seven Dolours of the Blessed Virgin Mary) the cemetery and chapel was consecrated by Bishop William Walsh.

As one historian has noted, the whole affair also “became a celebration of Walsh’s leadership and authority”. In a tremendous display of community cohesion, each procession had 1800-2000 participants, while large crowds gathered on the street to witness the display.

[Archbishop William Walsh, C., 1850]

The cemetery was laid out in sections, in both single and family plots. Special areas were designated for the clergy and religious congregations. The last burial in the old St. Peter’s cemetery was that of James Walsh, a native of County Cork, who expired on 8 February 1842. The first burials in Holy Cross Cemetery took place on 26 November 1843. On that unhappy afternoon, Daniel Mahar buried his three-year-old son John, and William Clancy buried his five-year-old daughter Catherine. In time many families had deceased members reinterred (from St. Peter’s) in the new graveyard, so that by 1846, some 500 souls were resting in the cemetery. One of those reinterred was Bishop Edmund Burke, vicar apostolic of Nova Scotia, who died in 1820.

Related Documents:

Susan Buggey, “Building Halifax, 1841-1871,” Acadiensis,10, No. 1 (1980): 90-112. (View Buggy Article)

Kim McGuire, “The Rural Cemetery Movement in Halifax, Nova Scotia.” (Honours Thesis, Saint Mary’s University, 1990) (View McGuire Thesis)