Greener Halifax

Feature stories from SMU School of the Environment faculty working to make Halifax a greener city.

Historical Development and Contemporary Significance of Halifax Parks

Dr. Jason Grek-Martin

Geography and Environmental Studies

|

|

|

Point Pleasant Park, |

Point Pleasant Park, |

Photo Credits: http://oceanstreasures.blogspot.ca/2009_11_01_archive.html

Dr. Jason Grek-Martin’s research blends cultural geography, environmental history, and environmental psychology to analyze the historical development and contemporary significance of two showcase Halifax parks. For a century and a half Point Pleasant Park has glittered as the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the city’s park system, while the Public Gardens have offered citizens and visitors alike an equally enriching natural oasis within the urban fabric of Halifax. While the origins of both parks can be traced to the 1860s, they nonetheless provide an interesting contrast because they embody two very different approaches to nature that were in cultural circulation at the time of their creation. The Public Gardens were (and are) the epitome of a particular Victorian focus on the highly-ornamental display of a carefully-ordered nature, whereas Point Pleasant Park exemplifies a more ‘naturalistic’ aesthetic that partially masks the necessary and extensive human interventions within the park landscape in order to offer the allure of an ‘urban wilderness.’

In addition, his research examines the recent, devastating impacts caused by Hurricane Juan (2003), particularly in Point Pleasant Park, where approximately 70% of the park’s trees were damaged or destroyed. Not surprisingly, the hurricane’s destructive impact generated powerful feelings of solastalgia for park users: a term created by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht to describe the distress caused by environmental degradation to a home place that once provided comfort and solace. Ultimately, this sense of loss was channeled into the public’s feedback during the 2005 international design competition, as users urged officials to restore the park’s wilderness aesthetic while endorsing an active management plan that would put the park on a sounder ecological footing. The forest has shown encouraging signs of regeneration over the past decade, which has helped Haligonians to forge meaningful new place attachments to their cherished urban park.

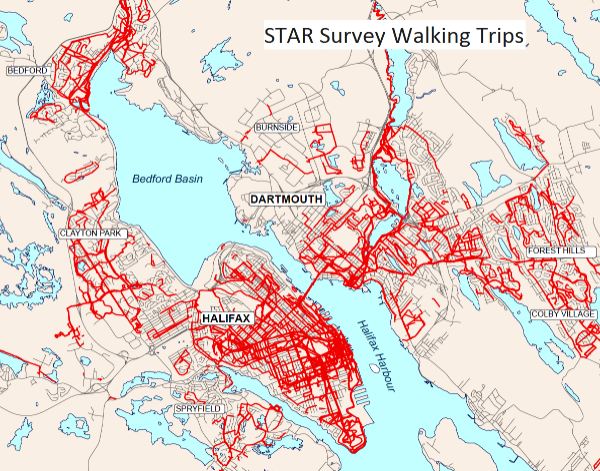

Building Walk-Friendly Communities

Dr. Hugh Millward

Geography and Environmental Studies

What factors affect the likelihood of walking rather than driving to urban destinations, and the frequency and length of walking trips? A research team at the SMU School of the Environment is investigating these questions in Halifax. Walking is important to citizens, urban planners, policy makers, and those in the public health, environmental, and transportation fields. More walking (and less driving) will improve public health, reduce transport infrastructure costs, and reduce the negative environmental impacts of transportation (notably, greenhouse gas emissions).

The team are focussing their research on Halifax, using time-use and travel data from the Halifax STAR (Space Time Activity Research) survey. Survey respondents completed a 48-hour time diary, with out-of-home activity monitored by a GPS unit. Walking episodes were reported on fewer than half the diary days, but those who walked were fairly active, averaging three active-transport (AT) walks and one recreational walk.

Both types of walk are important for healthy activity, but participation varies greatly by age, health status, and regional location.

For AT walks, people walk most frequently to their home, followed by their workplace. Other important destinations are bus-stops, restaurants and bars, grocery stores, shopping centers, and banks. Most AT walks are shorter than 600 m, and very few exceed 1200 m. Much walking occurs where jobs and services are densely clustered: 38% of all trips to downtown Halifax destinations are by the walking mode, whereas only 3% of trips to Burnside destinations are by walking.

Currently the team are mapping neigbourhood walking densities, and relating these to neighbourhood design features such as housing density, road connectivity, and land-use mix. Areas with a mix of employment uses and on-street retailing attract most walking.